The Allerum Dog, an 8,000-year-old canine skeleton unearthed in 1918 in Allerum Bog near Helsingborg, Sweden, offers insights into the role of dogs in Mesolithic hunting societies. The skeleton, studied by osteologist Elisabeth Iregren and archaeologist Kristina Jennbert from Lund University, reveals a flint-edged bone arrowhead lodged between its ribs, suggesting the dog was struck during a human-led hunt, later dying by a lakeshore and sinking into the bog.

Iregren’s 1993 study in Archaeofauna highlights the dog’s traits: an agile, wolf-like build with erect ears, a defined skull stop, strong shoulders, and a sturdy femur, adapted for hunting. Its fur, a mix of guard hairs and underfur, protected against cold and moisture. Evidence from Mesolithic sites like Skateholm, Sweden, shows dogs buried with humans, indicating their value as hunting partners. A 2011 study in Journal of Anthropological Archaeology notes isotopic data from Scandinavian dog remains, revealing diets high in marine protein, consistent with aiding hunters in coastal regions.

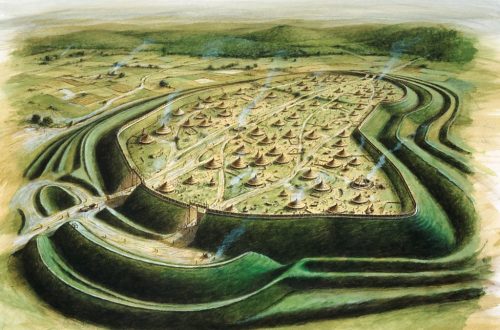

In later Neolithic societies, dogs continued to play a significant role. A 2018 study in PLOS ONE of Danish Ertebølle culture sites found dog remains with isotopic signatures (δ13C and δ15N) matching human diets, suggesting shared food resources and active hunting roles. However, at Çatalhöyük, Turkey, a 2016 study in the Journal of Archaeological Science identified dog bones with cut marks, indicating they were used for food, while others were buried with humans, suggesting a dual role as companions and workers.