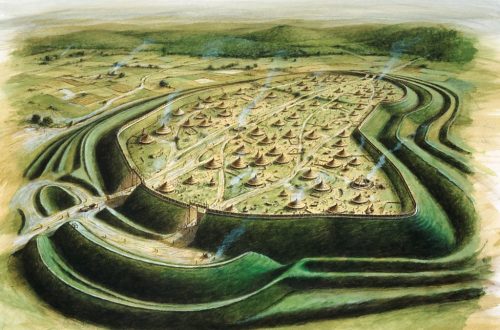

For over four centuries, the fate of the Lost Colony of Roanoke has remained one of America’s most enduring historical enigmas. In 1587, over 100 English settlers, led by Governor John White, established a colony on Roanoke Island, off the coast of present-day North Carolina. When White returned in 1590 after a three-year delay due to the Anglo-Spanish War, the colony was deserted, with only the word “CROATOAN” carved into a wooden post as a clue. Now, groundbreaking archaeological discoveries on Hatteras Island have provided compelling evidence that the colonists did not vanish but integrated with the local Croatoan tribe, solving a mystery that has puzzled historians and archaeologists for generations.

The Roanoke expedition, backed by Queen Elizabeth I and Sir Walter Raleigh, aimed to establish England’s first permanent settlement in the New World. The 1587 group comprised 118 men, women, and children, including families, signalling a long-term commitment to colonisation. Among them was Eleanor White Dare, John White’s daughter, who gave birth to Virginia Dare, the first English child born in America. The settlers faced harsh conditions, including food shortages and tense relations with some local Native American tribes. However, they formed a friendly relationship with the Croatoan tribe near Hatteras Island.

When White sailed back to England for supplies in late 1587, he expected to return quickly. However, the Anglo-Spanish War delayed his voyage, and by the time he reached Roanoke in 1590, the settlers were gone. The cryptic “CROATOAN” carving suggested they may have relocated to Hatteras Island, but no definitive evidence was found at the time, giving rise to theories of disease, massacre, or assimilation.

Recent excavations led by archaeologists Mark Horton and Scott Dawson on Hatteras Island have uncovered what they describe as “smoking gun” evidence of the colonists’ fate. Working for over a decade, the team discovered buckets of hammerscale—tiny flecks of oxidised metal, no larger than a grain of rice, produced during metal forging. These artefacts, unique to 16th-century European metalworking, were found in significant quantities at a site on Hatteras Island, indicating the presence of skilled English craftsmen among the Croatoan tribe.

Additional finds, including lead shot and English ceramic artefacts, further support the theory that the Roanoke settlers relocated to Hatteras and lived alongside the Croatoan people. Unlike coins or sword hilts, which could have been traded, hammerscale is a direct byproduct of on-site metalworking, making it a definitive marker of English presence. According to Horton, “These flecks of oxidised metal are the ‘smoking gun’ evidence of what happened to the Roanoke settlers”.

The discoveries align with historical accounts suggesting the colonists planned to move to a more sustainable location. The word “CROATOAN” carved at the Roanoke site likely indicated their destination, as the Croatoan tribe was known to be friendly and had interacted with the settlers during their time on Roanoke.

The Hatteras findings build on earlier discoveries that hinted at the colonists’ movements. In 1937, the Dare Stone was unearthed in North Carolina, bearing an inscription attributed to Eleanor White Dare. The stone, marked with a cross symbolising distress, stated, “Ananias Dare & Virginia Went Hence Unto Heaven 1591 / Anye Englishman Shew John White Govr Via,” suggesting some settlers survived at least until 1591. While the stone’s authenticity has been debated, it complements the new archaeological evidence pointing to Hatteras.

In 2012, researchers at the British Museum analysed John White’s 400-year-old “La Virginea Pars” map using a lightbox. They discovered a hidden fort symbol in Bertie County, North Carolina, where English ceramics were later found. This site, called Site X, likely served as a temporary refuge for some settlers before moving to Hatteras. The First Colony Foundation, which has led investigations at Site X and Hatteras, believes these artefacts confirm the colonists’ gradual dispersal and integration with Native American communities.

The new evidence challenges the narrative of a “lost” colony, suggesting a story of adaptation and survival instead. Archaeologist Scott Dawson, who has long argued against a mysterious disappearance, emphasises that the settlers likely chose to assimilate with the Croatoan tribe to ensure their survival. “The Lost Colony of Roanoke didn’t disappear—they moved and lived alongside the Croatoan tribe,” Dawson stated at a recent talk at the Roanoke River Maritime Museum.

The Hatteras discoveries mark a significant breakthrough, but questions remain. The First Colony Foundation plans to excavate Site X and Hatteras to uncover more artefacts and clarify the settlers’ interactions with the Croatoan tribe. Given the settlers’ struggles with food and conflicts with other tribes, researchers are particularly interested in whether the assimilation was voluntary or driven by necessity.

The findings also prompt a reevaluation of early colonial history, highlighting the complex relationships between European settlers and Native Americans. Rather than a tragic vanishing, the Roanoke story may reflect resilience and cultural exchange, with the settlers adopting Native American practices to survive in a challenging environment.